|

Reproduced from an article

by Helen M. Leach From The New Zealand

Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture),

Vol. 1, No. 2, June 1996, pp. 12-18. The second tradition to reach New Zealand was the European. By two thousand years ago it had amalgamated the gardening styles of the Romans with the indigenous plant lore of local tribes in Western Europe. By 1300 AD it had accommodated ideas and new plants from the Islamic world, and it then went on to assimilate a whole raft of new plants (but not concepts) from the Americas and the Far East in the last few hundred years before the tradition was transplanted to New Zealand. As a temporal and cultural unit, the tradition is most suited to discussing changes in garden history that are compared over hundreds of years, and involve contact and interaction between diverse cultures. To my knowledge, the concept of the tradition has not been invoked in any systematic way in analyses of garden history in European countries, despite the fact that their time depth of human occupation is greater than that of New Zealand. Instead, named styles have been the dominant unit of analysis in the literature. Readers of English garden history should be familiar with the following simplified sequence (Table 1). Although these styles have come to 'represent' English garden history, they are in fact highly restricted in their application. Firstly, they refer to the ornamental/pleasure garden or park, not to the kitchen garden or domestic orchard. Secondly, they relate to the ornamental gardens created for or by wealthy landowners. Essentially these are 'designer garden' styles, although the growth of the middle classes saw attempts to disarticulate them into forms and elements suitable for smaller suburban villa and town gardens. Such a trickle-down effect is widely recognised in all human activities subject to the fashion phenomenon. But the copying of what was originally conceived of as a stylistic unity for a particular landscape, with its own philosophical connotations, dilutes the original meaning of the design to a mere collection of elements without symbolic coherence. Thus much of the original meaning of the style is lost, though as I will argue later, the elements can be very long lasting and may outlive their style.

Table

1. Chronological table of English garden history analysed by style. Further problems with analysis according to style were pointed out by Kenneth Woodbridge in 1979:

Styles from the last

three centuries before the 20th century are invariably associated

with key individuals (writers, philosophers, designers, practitioners

and talented amateurs) and often with specific gardens and characteristic

elements (such as the ha-ha in the early phase of the English Style).

In combination, these elements are often treated as the signature

of the style. As can be seen from Table 1, earlier styles are more

often referred to by reference to the reigning royal house, and

appear to have lasted longer. Is this shortening of the duration

of a style through history a factor of increasing rates of change

stimulated by a growing population and more communication, or is

it an artefact of document survival? The leading historian of medieval

English gardening, John Harvey, believes that stylistic changes

occurred within that period, but we are too far away in time to

see anything but the overall pattern and the long view (Harvey 1986).

Conversely, we are probably too close to the changes of the 20th

century to recognise clearly the styles that have prevailed since

the First World War. Can any of us answer the following questions?

Are our New Zealand home gardens gardenesque in style, formal revivalist,

or naturalistic, or all three? Is an informal garden of natives

a direct descendant of the picturesque style garden, or representative

of William Robinson's naturalistic, or the forerunner of the new

ecological style? A more fundamental question

would be to ask whether any garden that has not been designed as

a unity, conforming to a particular philosophy of gardening or landscaping,

can be said to have a style. Of course if the answer is no, that

would rule out all the home gardens that have been subject to piecemeal

and progressive alterations. I believe that the great majority of

New Zealand home (and public) gardens consist of elements,

derived and selected from the whole range of previous and extant

styles. It is significant in this respect that the small but growing

literature on New Zealand garden history has found it very difficult

to apply English style names appropriately or consistently. Rather than struggling with styles as a framework for New Zealand garden history, we could usefully adopt an element-based approach which will not only reflect the gardeners' own selection processes, but will reveal the rise and fall in popularity of each component without tying it to a particular style. Elements of the garden include both plants and structural features. A good start has been made documenting the history of the introduction of particular species and garden varieties to New Zealand, and recording the progress made by local breeders and selectors (e.g. Challenger 1986/7; Nobbs 1988; Shepherd 1990; Rooney 1993). However the history of garden structural features has scarcely been touched. It has to be extracted from dated descriptions of gardens, catalogues and advertisements, and from gardening books and pamphlets written in New Zealand. Preliminary studies that I have made in this area suggest that it will be valuable to compare the period of popularity of each selected feature with that observed in Britain, the country which has most influenced New Zealand home and public gardens. Some elements, like lakes, chains of ponds, rustic bridges, bush walks, avenue driveways, and ha-has, belong to larger gardens of the type made for country homesteads or urban parks. Others which I will review below were of a more flexible scale and could be adapted for smaller town and suburban home gardens.

From the 1840s shrubberies were an integral part of New Zealand gardens. Felton Mathew's property in Auckland had a lawn with inset flower beds, sloping down to a shrubbery consisting of mixed natives and exotics (Cooper 1972: 28). Felix Wakefield's advice in 1870 to avoid eucalypts in shrubberies gives some indication of the size of what could be included in a Victorian shrubbery (Wakefield 1870). Matthews' catalogue of New Zealand flora of c.1893 recommended certain native species like Drimys (Pseudowintera) and Melicytus "for the ornamental shrubbery". The popular New Zealand garden writer Michael Murphy (1907: 237, 246) provided lists of trees and shrubs for the shrubberies of small gardens and noted that ornamental grasses could be included. The one-eighth acre garden plan provided by A. E. Lowe (1915: 21 - 2) in 1915 shows shrubs on one side of the small front lawn. In the spirit of the new era David Tannock (c.1914: 144) criticised the former choice of shrubs, specifically targetting laurels, laurestinus, ponticum rhododendrons, variegated hollies and "solemn looking cupressus". He argued that flowering and ornamental foliage shrubs were ideal for banks and terraces, and broke up the garden interior so that the garden actually looked bigger, an equally important consideration to the Victorians before him (Tannock c.1914: 23). A shrubbery also provided excellent screening so that the front door could not be seen from the front gate (Tannock c.1914: 24), again a Victorian preoccupation, but this time with privacy rather than with the size of one's property. After the First World War, the shrubbery began to lose its separate identity in both New Zealand and English gardens. Young and Hay (1919: 33) wrote that while shrubs used to be massed together into shrubberies which contained too many commonplace plants like laurels, the new trend was towards shrub-beds and shrub-borders. There was increasing interest in selecting shrubs for all year colour (Home & Building 1938 3(1): 45), and in combining shrubs with perennials in a mixed shrubbery border (Building Today 1937 1(2): 41). After the Second World War the outdoor room analogy became popular in New Zealand garden writing, and mixed borders of flowers and shrubs were seen as providing the essential background furnishings to the outdoor living room (Elliott 1947: 540 - 1; Salinger et al. 1962:87). Although massed plantings of rhododendrons, or Australian or South African shrubs became relatively common in larger gardens, they were no longer described as shrubberies. In fact the term seems to have dropped from common use in the 1940s. Overall, the shrubbery lasted nearly two hundred years (1750 - 1950) as a significant, named garden element.

The

Victorian period witnessed an episode of pteridomania which peaked

in the 1850s (Allen 1969: x, 72). Horticulturally it took three forms:

miniature ferneries in Wardian cases, fern houses (greenhouses dedicated

to fern cultivation) and outdoor ferneries. One of the first British

examples of the use of the term fernery was by Newman in 1840. He

was referring to an outdoor rockery specially designed to hold ferns

(Allen 1969: 70). Charles McIntosh (1853: 667) gave a combined entry

to 'The Fernery and Muscarium' in 1853, noting that "many ladies now

bestow great attention on ferns" to the extent that a specialist nursery

trade was developing. At the height of the craze, many conservatories

were furnished with rock mounds covered in ferns. Just such a display,

with a fountain at the summit, was mounted at the Floral and Horticultural

Show in Auckland in 1857 (Cooper 1972: 35). It is thus clear that

New Zealand gardeners were not slow to adopt the fashion. The

Victorian period witnessed an episode of pteridomania which peaked

in the 1850s (Allen 1969: x, 72). Horticulturally it took three forms:

miniature ferneries in Wardian cases, fern houses (greenhouses dedicated

to fern cultivation) and outdoor ferneries. One of the first British

examples of the use of the term fernery was by Newman in 1840. He

was referring to an outdoor rockery specially designed to hold ferns

(Allen 1969: 70). Charles McIntosh (1853: 667) gave a combined entry

to 'The Fernery and Muscarium' in 1853, noting that "many ladies now

bestow great attention on ferns" to the extent that a specialist nursery

trade was developing. At the height of the craze, many conservatories

were furnished with rock mounds covered in ferns. Just such a display,

with a fountain at the summit, was mounted at the Floral and Horticultural

Show in Auckland in 1857 (Cooper 1972: 35). It is thus clear that

New Zealand gardeners were not slow to adopt the fashion.Outdoor ferneries survived longer in Britain than their indoor counterparts, being made from the 1840s into the early 20th century, in the form of glens or rockeries. The reason for their survival may be their association after 1870 with the natural or wild garden concepts promoted by William Robinson. Robinson believed that it was more natural to mix ferns with flowers, but figured a rock fernery of the 'pure' type (Fig. 1) in his book The English Flower Garden (Robinson 1893: 131). The doyen of the formal architectural school, Thomas Mawson, dismissed the fernery in one line as a "specialised branch of wild gardening" (Mawson 1912: 212). The wealth of fern species in New Zealand undoubtedly contributed to the success of ferneries here. Thelma Strongman (1984: 89, 131 - 2) referred to an outdoor fernery in Christchurch in the 1870s-80s and at Mt. Peel by 1887. By public request Michael Murphy enlarged his section on fern growing in the second edition of his best-selling book Handbook of New Zealand Gardening, c.1888. He wrote:

D. Tannock described a more naturalistic outdoor fernery in 1914:

While Tannock's and later

Cockayne's ideal fernery took the form of an open-air and naturalistic

setting for ferns, there is evidence of popular interest in the

fernery as an actual construction. Tipples (1989: 101 - 4, 106)

described and illustrated elaborate rock and metal-framed ferneries

designed and built for wealthy clients by Buxton in 1914 and 1930-4.

The poor man's equivalent was outlined by Young and Hay in 1919: Cockayne (1923: 104) considered such artificial structures to be ugly, preferring to grow ferns in the shade of trees. Whether the extraordinary Buxton ferneries of the 1930s fit Allen's term 'hypertrophy' and 'over-extension' and other trends to the 'extreme abnormal' which he believes mark the close of a fashion (Allen 1969: 57), there is little evidence that there was any further demand for the fernery as a distinct garden element in New Zealand after the Second World War. I have found only one post-war reference, and this, not surprisingly, was in Muriel Fisher's book on Gardening with New Zealand Plants, Shrubs and Trees (1970: 209). The decline of the fernery does not imply that ferns will be neglected in the gardens of the future. Today there are signs that ferns are being integrated with other native plants in groupings based on ecological associations. The ecological garden of the 21st century should see a strengthening of this trend.

As

a garden structure, the pergola is much younger than the fernery.

It provides a good example of the speed with which a fashionable element

was adopted in Britain and soon after, in New Zealand. Although early

Victorian gardens had rose arches and trellised coverings to paths,

which served to screen walkers from undesirable views (e.g. McIntosh

1853: 685), the pillared pergola appeared in Britain only towards

the end of the 19th century. William Robinson recommended the adoption

of both simple wooden pergolas using oak supporting posts, and the

more stately examples with stone columns, both of which he had observed

in Italy. A brick-pillared pergola (probably designed by Lutyens)

was a feature of Gertrude Jekyll's garden at Munstead Wood (Fig. 2),

and it was figured in Robinson's 1893 edition of The English Flower

Garden (Robinson 1893: 152). Architectural pergolas became frequent

components of Mawson's designs and his work influenced Buxton and

Taylor in New Zealand. Tipples commented: As

a garden structure, the pergola is much younger than the fernery.

It provides a good example of the speed with which a fashionable element

was adopted in Britain and soon after, in New Zealand. Although early

Victorian gardens had rose arches and trellised coverings to paths,

which served to screen walkers from undesirable views (e.g. McIntosh

1853: 685), the pillared pergola appeared in Britain only towards

the end of the 19th century. William Robinson recommended the adoption

of both simple wooden pergolas using oak supporting posts, and the

more stately examples with stone columns, both of which he had observed

in Italy. A brick-pillared pergola (probably designed by Lutyens)

was a feature of Gertrude Jekyll's garden at Munstead Wood (Fig. 2),

and it was figured in Robinson's 1893 edition of The English Flower

Garden (Robinson 1893: 152). Architectural pergolas became frequent

components of Mawson's designs and his work influenced Buxton and

Taylor in New Zealand. Tipples commented:

This feature was not

confined to the wealthy, however. Home-made pergolas were easy to

construct, with the ubiquitous manuka pole providing a suitably

rustic appearance. About 1914, David Tannock was of the opinion

that:

Pergolas have continued

in use in New Zealand right through to the 1990s. Three factors

have aided their survival as a garden element. In the 1970s, the

desire for indoor-outdoor living saw the explosion of decks and

renewed interest in pergolas (Barnett 1993: 6). In the 1990s the

trend to small formal courtyard gardens of Mediterranean flavour

has also increased the demand for the pergola's shade-giving properties

and the opportunities it provides for vertical planting in a small

space. Thirdly, the development of timber preservatives has dramatically

increased their garden life span. In short the pergola is likely

to endure well into the 21st century as a garden element well adapted

to modern life-styles and garden use.

The spaces between the

stones or slabs he considered ideal for dwarf spreading and alpine

plants (idem). By 1932, however, English canons of taste

prescribed its use with formal architecture. The influential Studio

Garden Annual stated that for country houses:

In neither Britain nor New Zealand did crazy paving remain fashionable after the war, possibly because it was labour-intensive to weed, and could not be laid as quickly as other path surfaces. The craze seems to have developed and waned in the space of three or four decades at the most.

The

concept of gardening within the earth-filled pockets of a group of

'introduced' rocks appears to have 19th century origins in Britain,

although rock structures as landscape features to display the rocks

themselves can be traced to the 18th century (Hunt 1986: 11). Rocks

had been used extensively for grottoes and cascades in the 18th century

English Rococo Garden (Symes 1991). In the Regency and early Victorian

periods extraordinary heaps of assorted stones, vitrified bricks,

glass debris, shells or old tree roots became popular (Stuarty 1988:186).

These seem to have been more in the spirit of the 18th century rock

creations than as a setting for plants. Where plants were described,

they were generally ferns chosen for their picturesque and romantic

associations. Increasing upper class interest in travel in the European

Alps eventually created a demand for alpine plants rather than ferns,

and the recreation of Alpine rather than Highland scenery. The

concept of gardening within the earth-filled pockets of a group of

'introduced' rocks appears to have 19th century origins in Britain,

although rock structures as landscape features to display the rocks

themselves can be traced to the 18th century (Hunt 1986: 11). Rocks

had been used extensively for grottoes and cascades in the 18th century

English Rococo Garden (Symes 1991). In the Regency and early Victorian

periods extraordinary heaps of assorted stones, vitrified bricks,

glass debris, shells or old tree roots became popular (Stuarty 1988:186).

These seem to have been more in the spirit of the 18th century rock

creations than as a setting for plants. Where plants were described,

they were generally ferns chosen for their picturesque and romantic

associations. Increasing upper class interest in travel in the European

Alps eventually created a demand for alpine plants rather than ferns,

and the recreation of Alpine rather than Highland scenery.The popular garden writers railed against the lack of taste of most rockeries (e.g. McIntosh 1853: 701) while praising rockeries that seem equally incongruous today, such as Lady Broughton's 34 foot high reconstruction of the Alps at Chamonix which rose out of her garden lawn near Chester. It was built from limestone, quartz and spar, with broken white marble chips to simulate snow, and alpine plants inserted into the lower portions (McIntosh 1853: 702). To McIntosh and the other Victorian garden writers, rockeries served as useful screens, gave an illusion of space in town gardens, covered barren banks (Victorians were troubled by unclothed surfaces), and imitated desirable natural features (McIntosh 1853: 704). Despite the continued British interest in this element, which gained more impetus from Robinson's backing in the 1880s, there is little evidence that the rockery was an important component of New Zealand gardens until the end of the 19th century. The Matthews' catalogue of New Zealand flora of c.1893 refers to particular natives as suitable for rockeries, yet the newspaper description of their Hawthorn Hill 'show' garden in 1878 (Otago Witness 16/2/1878 p.21) fails to mention any such feature. They were however, a prominent item in this garden by 1922 (Otago Witness 25/4/1922 p.7, 33). I suspect they were created by John McIntyre in the 1890s to house the growing collection of alpines that he and Henry Matthews had gathered from the wild. By 1914, it seems that rock gardens were becoming very popular. David Tannock wrote:

Although Tannock was

referring to both Britain and New Zealand, there is no real evidence

that this fashion was being led from Britain, for rock gardening

advice seems to have been more prevalent in New Zealand-authored

books of the post-war period than in the contemporary British literature.

For example, the New Zealand writers Young and Hay (1919: 97) wrote

that:

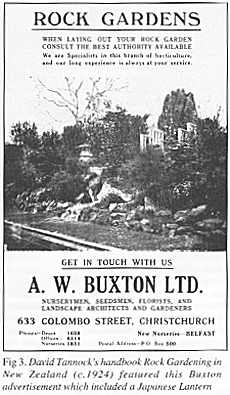

Cockayne (1923: 24) stressed

the value of rockeries as sites for growing and displaying native

alpines, while a year later Tannock devoted a whole book to Rock

Gardening in New Zealand (c.1924). It featured an advertisement

by Alfred Buxton (Fig. 3) offering the firm's services for the design

and construction of rock gardens. Buxton's rock gardens fall mainly

in the period 1919-1937 (Tipples 1989: 68, 70). Though the enthusiasm for rock gardening may have waned in the 1930s (perhaps as the rockeries of the 1915-25 period became progressively over-run with weeds such as oxalis and couch grass), they continued in use well after the Second World War. As with the mixed border, however, there was a tendency to increase the variety of plant types in them from the late 1930s. Dwarf conifers and other small shrubs were added to existing rockeries to provide contrast and height (Building Today 1937 1 (2): 45; New Zealand Gardener 1946 3(10): 549). By the 1970s whole rockeries were dedicated to conifers and the work of caring for dwarf alpines had been eliminated, along with the alpines, by mats of plastic and increasingly replaced by bark since the 1980s. It is not surprising that new rockeries of the traditional type have been a rare phenomenon since the 1980s. Rock settings for a wider variety of ecological planting will probably be the form in which rockeries make the transition into the 21st century.

There are many other structural elements of gardens that deserve analysis, elements like sunken gardens, herb gardens, herbaceous borders, lily ponds, rustic garden furniture, formal roseries, gazebos, sundials, fountains, birdbaths, and patios. Popularity has also waxed and waned for the other main category of garden element, the plants themselves. For example, the late 19th century saw a fashion for dressing the fronts of houses with climbers and creepers, while at the same period statuesque sub-tropical plants provided centrepieces for flower beds cut out of the lawns. Like certain structural elements some plant genera such as roses have had an appeal which spans centuries, though particular named varieties of roses have had popularity spans of less than a decade. In this case the cultivation of the rose genus could be treated as a marker of the European tradition. The currently fashionable ground-cover roses should probably be interpreted as a short-term element similar to crazy paving. Although the nursery trade strongly influences through its advertising the initial phase of popularisation of particular varieties, the duration of the fashion is much less subject to trade control. It may depend on such shifting public sentiments as nostalgia, boredom, anxiety, or excitement. Functional considerations are also relevant, such as the labour costs of maintenance, or changes in garden size. My preliminary study has confirmed that like the plants, the structural elements of gardens show great variation in their time span of utilisation and popularity. They appear to have an existence which though influenced by the designer styles is nevertheless quite separate. They frequently outlive the styles with which they were first associated, and often become elements of successive styles. This phenomenon also applies to indoor decorative elements such as furniture and furnishings. It is probably only explicable by looking at the meaning that the element held for each user in the light of the popular literature of the time, the tastes for art, rules of etiquette, feelings about social class and race, and even nationalism (c.f. Leach 1994). For the future, analysis of the meaning of garden elements offers us the opportunity to look at the history of gardening in its widest social context rather than confining ourselves to the arbitrary and artificial framework imposed by styles. Bibliography Allen, D. E. 1969 The Victorian Fern Craze: A History of Pteridomania. Hutchinson, London. Barnett, R. 1993 Garden Style in New Zealand. Random House NZ Ltd, Auckland. Blook, A. 1974 Conifers for your Garden. Floraprint, Calverton, Nottingham.. Challenger, S. 1986/7 Commercial Availability of Conifers in N.Z. 1851 - 1873. Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture Annual Journal 14: 76 - 85. Cobbett, W. 1829 The English Gardener. [Oxford University Press ed. 1980 intro. by A. Huxley]. Cockayne, L. 1923 The Cultivation of New Zealand Plants. Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, Christchurch. Cooper, R. C. 1972 Early Auckland Gardens. Garden History 1(2): 26 - 40. Elliott, D. 1947 Planning the Small Town Garden for Use, Convenience and Enjoyment. New Zealand Gardener 3(10): 537 - 541. Fisher, M. E., E. Satchell and J. M. Watkins 1970 Gardening with New Zealand Plants Shrubs and Trees. Collins, Auckland. Harvey, J. 1986 England. Medieval Gardens. pp 163 - 4 In G. Jellicoe et al. q.v. Harvey, J. 1988 Restoring Period Gardens from the Middle Ages to Georgian Times. Shire Garden History No.l. Haverfordwest. Hunt, P. E. 1986 Alpine, scree, and rock garden. pp 11 - 13 In G. Jellicoe et al. q.v. Izzard, P. W. D. 1932 The Country Garden. pp 3- 34 In F. A. Mercer (ed.) Gardens and Gardening The Studio Garden Annual. The Studio Ltd, London. Jellicoe, G., S. Jellicoe, P. Goode and M. Lancaster (eds) 1986 The Oxford Companion to Gardens. Oxford University Press. Leach, H. M. 1984 1,000 Years of Gardening in N.Z. Reed, Wellington. Leach, H. M. 1994 Native Plants and National Identity in N.Z. Gardening: an Historical Review, Horticulture in N.Z. 5(1): 28 - 33. Lowe, A. E. ('Aotea') 1915 The Sun Gardening Book. Canterbury Publishing Co., Christchurch. McIntosh, C. 1853 The book of the Garden. Vol. 1 - Structural. William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh. Matthews Descriptive and priced Catalogue: Ferns, Seeds, Plants and Shrubs, Trees of New Zealand Flora. c.1893. [Otago Settlers Museum Archives] Mawson, T. H. 1912 The Art and Craft of Garden Making. 4th ed. Batsford, London. Murphy, M. 1907 Gardening in New Zealand. 4th ed. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch. Nobbs, K. J. 1988 Where did our first Exotic Plants come from? Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture Annual Journal 15: 104 - 106. Robinson, W. 1893 The English Flower Garden...3rd ed. John Murray, London. Rooney, D. 1993 Stem and Branch: Patterns of Tree-Planting in Central Canterbury since 1852. Part 1. The Banks Peninsula Area. Horticulture in N.Z. 4(1): 4 - 6. Part 2. The Plains. 4(2) 20- 22. Salinger, J. P., J. S. Say and K. H. Marcussen 1962 Flower Gardening with the Journal of Agriculture. Whitcombe and Tombs, N.Z. Salinger, J. P. 1971 The New Zealander's Guide to Pebble Gardens. Collins, Auckland. Shepherd, R. W. 1990 Early importations of Pinus radiata to New Zealand and distribution in Canterbury to 1885: implications for the genetic makeup of Pinus radiata stocks. Part 1. Horticulture in New Zealand 1(l): 33 - 38. Part II 1(2): 28 - 35. Strongman, T. 1984 The Gardens of Canterbury: A History. Reed, Wellington. Stuart, D. 1988 The Garden Triumphant: A Victorian Legacy. Viking, London. Symes, M. 1991 The English Rococo Garden. Shire Garden History No. 5. Havodordwest. Tannock, D. c.1914 Manual of Gardening in N.Z. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch. Tannock, D. c.1924 Rock Gardening in New Zealand. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch. Tannock, D. c.1934 Practical Gardening in New Zealand. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch. Tipples, R. 1989 Colonial Landscape Gardener Alfred Buxton of Christchurch, New Zealand 1872 - 1950. Department of Horticulture and Landscape, Lincoln College, Canterbury, N.Z. Trenberth, K. E. 1977 Climate and Climatic Change: A New Zealand Perspective. N.Z. Meteorological Service Miscellaneous Publication 161. Wakefield, F. 1870 The Gardeners Chronicle for New Zealand. Thomas McKenzie, Wellington. White, G. 1975 Garden Kalendar 1751 - 1771. Scolar Press, London. Woodbridge, K. 1983 The Nomenclature of Style in Garden History. Eighteenth Century 8 n.s. (2): 19 - 25. Young, J. and D. A. Hay 1919 Flower Gardening in N.Z. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch. Acknowledgements I wish to express my sincere thanks to the Wellington Branch of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture for their invitation to give the 1995 Ian Galloway Memorial Lecture.

|

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2025 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: August 3, 2001