|

The

significance of rengarenga

From The New Zealand

Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture),

Vol. 1, No. 2, June 1996, pp. 19-21.

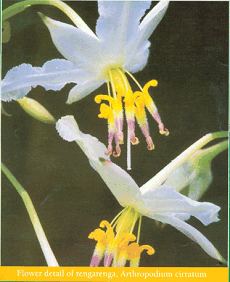

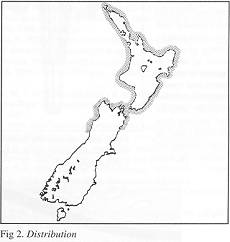

The paper discusses the importance of rengarenga to Maori and evidence outlining the use of the plant as a food source and for medicinal, spiritual and other cultural purposes including its representation in kowhaiwhai patterns is presented based on historical and recent documents, and oral history. Introduction Rengarenga Arthropodium

cirratum is a lily which colonises rocky coastal areas from

the North Cape to a southern limit from Kaikoura to Greymouth. It

is often referred to as the New Zealand rock lily. An alternative Maori

name for the plant, maikaika, is shared with two native orchids

(Orthocerus strictum and Thelymitra pulchella)

that have similar starchy, edible root-like tubers. (Crowe

1995). Rengarenga is not common

in the wild in some regions of its habitat and is classified by

the Department of Conservation as being vulnerable in the Wellington

conservancy. The plant forms extensive colonies and in summer bears

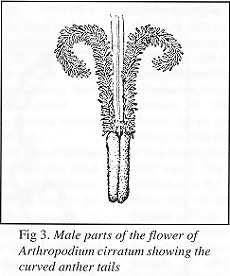

panicles of six petalled white flowers on 30 cm stalks. The flowers

have purple and yellow stamens which are curled at the ends and

give rise to the specific name cirratum (curled). Significance to Maori Information about the

importance of rengarenga as a food source for Maori and its cultural

and spiritual significance was recorded by William Colenso who,

along with Elsdon Best, published much of the early ethnobotanical1

information in New Zealand. Colenso also recorded information about

the medicinal properties of the plant and how it was utilised by

Maori for that purpose.

Spiritual

Kerr 1995 (pers. comm.) stated that this proverb relates to the Maori land wars of the 1860's in the Waikato when the Waikato Maori were being forced back into the King Country and were threatened with the loss of their land. The proverb means - even though we may be dispossessed, we will survive on what we can gather from the fruits of the land. Riley (1994: 116) noted

in Maori Healing and Herbal - New Zealand Ethnobotanical Sourcebook,

that an inner meaning indicates that men as fodder for the controller

of war, Tu, will be plentiful for that purpose. It is claimed that

the spirits of such warriors, when killed in war, travelled to Cape

Reinga in great style, carrying weapons, dancing and talking and

making much noise. The spirits of those dying of natural causes,

on the other hand, travelled to Cape Reinga silently waving branches

of rengarenga as they moved. Riley also noted that rengarenga once

lay in a place of honour on the tuahu (sacred place) at Whangara

(north of Gisborne). Kowhaiwhai patterns

Neich 1993: 34 noted

that some, have mythological associations and that the chief connotation

of kowhaiwhai seems to relate to ideas of genealogy and descent.

The rengarenga flower is represented in several kowhaiwhai patterns

underlining the significance of the plant to Maori. Colenso 1891: 460 in

describing kowhaiwhai patterns wrote: "One in particular,

I may mention and explain: this pattern was called rengarenga, from

being an imitation of, or an ideal association with the curved anthers

of the flowers of that plant, the New Zealand lily (Arthropodium

cirratum). Here we have another curious and pleasing instance

of coincidence of ideas in natural close observation and naming

between two widely opposite peoples, the ancient New Zealander and

the highly civilised European — the German botanist

Forster who accompanied Cook on his second voyage to New Zealand

and who gave the appropriate specific name of cirratum to this plant

from its peculiar closely-curved and revolute anthers" (see fig

3). Despite an extensive

search, the kowhaiwhai pattern described by Colenso could not be

located nor could any other patterns incorporating rengarenga anther

patterns. Simmons 1995 (pers. comm.)

noted that the flowers of the rengarenga plant were sometimes incorporated

into other kowhaiwhai patterns3 such as that shown

in Fig 4. This was in the house Te Poho o Haraina which

stood at Patutahi near Gisborne and was the house of Wi Pere

of the Rongowhakaata iwi. It was opened in 1885 and

burnt down in 1947. The basic pattern is similar to that identified

by Hamilton 1896: 127, as Ngutukura (the whale) but this

version incorporates stylised rengarenga flowers. Simmons indicated

that these four petalled flowers (rengarenga actually has six petals)

were known as popoa rengarenga and refer to the gods, whereas

flowers with more than four petals refer to men. The pattern shown in

Fig 5, is reported by Simmons to be from a house in the Bay of Plenty-East

Coast area and was painted on narrow flat rafters. Simmons noted

that the stalks and unopened flowers of rengarenga were rendered

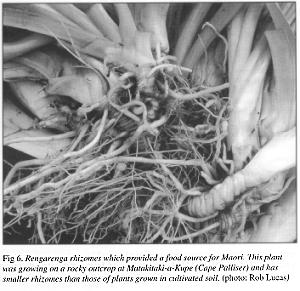

quite realistically. Food Colenso (1880: 30) recorded

that rengarenga was one of the few native plants cultivated by Maori

for food. He wrote: "The thick fleshy roots

of the New Zealand lily Arthropodium cirratum, were also

formerly eaten, cooked in the earth oven. This plant grows to a

very large size in suitable soil, and when cultivated in gardens.

From this circumstance, and from not unfrequently noticed it about

old deserted residences and cultivations, I am inclined to believe

that it was also cultivated." The author observed that

wild plants growing in their natural habitat tend to produce small

tightly congested rhizomes and often grow on rock faces almost like

epiphytes, whereas the same plants grown in cultivated soil, produce

much larger rhizomes. Riley 1994: 416 noted

that rengarenga rhizomes when roasted or cooked in a steam oven

(umu) have a flavour not unlike potato. This was confirmed by the

author who reported that after steaming rhizomes for 60 minutes,

the younger sections nearest the growing points, were soft and tender,

while the older more mature sections were very fibrous and not as

palatable. The rhizomes of a related plant, vanilla lily Arthropodium milleflorum are eaten by Australian Aborigines (Sainty l989: 46). Medicinal Maori were highly skilled

in using herbs in conjunction with spiritual healing (Riley 1994:

9). Riley noted that boils

and abscesses were one of the main surgical complaints that afflicted

Maori in pre-European times and into the early 20th century and

referred to the report of the Colonial Hospital Wellington, for

the year 1848 which listed abscesses as fourth equal with lung inflammation

as cause of death among Maori patients. Riley also noted in Maori

Healing and Herbal that "no less one-fifth of the

some 200 plants in this book are used to treat boils and abscesses."

More recent publications

on medicinal uses of native plants including Riley 1994, and Brooker

et al. 1981: 63, refer to the above two publications (White

and Colenso) for medicinal uses of Arthropodium cirratum. Enquiries made by the author indicate that rengarenga does not appear to be used for medicinal purposes today. Notes

Acknowledgments The following individuals provided assistance and advice in the preparation of this study:

References Brooker, S.G., R.C. Cambie and R.C. Cooper. 1981. New Zealand Medicinal Plants. Auckland: Heinemann Publishers. Colenso, W. 1868. Geographic and Economic Botany of the North Island of New Zealand. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 1: 232-83. Colenso, W, 1880. On the Vegetable Food of the Ancient New Zealanders. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 13: 338. Colenso, W. 1891. Reminiscence of the Ancient Maoris. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 24: 460. Crowe, A. 1995. Which Coastal Plant? Auckland: Viking New Zealand. Department of Conservation Wellington Conservancy Draft Conservation Management Strategy 1994-2003. 1994 Volume 1. Appendix 1. PO Box 5086, Wellington. Hamilton, A. 1896. The Art Workmanship of the Maori Race in New Zealand. Dunedin: Fergusson and Mitchell. University of Otago. Kerr, Hoturoa. 1995. personal communication. Neich, R. 1993. Painted Histories. Auckland: Auckland University Press. Parsons, M.J. 1992. Ethnobotany — A Maori Perspective. Proceedings of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture Annual Conference 1992. Riley, M. 1994. Maori Healing and Herbal. New Zealand Ethnobotanical Sourcebook. Paraparaumu, New Zealand: Viking Sevenseas. Sainty, G.R. 1989. Wildthings, plants and animals commonly seen around Sydney. Sydney, Australia: Sainty and Associates. Simmons, D.R. 1995. personal communication. Tregear, E. 1904. The Maori Race. Whanganui: A.D.Willis. White, J. 1883. Maori Pharmocopia. MS Papers 75 B35/11 Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. Williams, H.W. 1992. Dictionary of the Maori Language. 7th edition. Government Print Publications Ltd.

Web-notes:

|

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2024 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: March 1, 2021

Reproduced

from an article by the late Graham Harris

Reproduced

from an article by the late Graham Harris Rengarenga

is recorded by Tregear (1926: 496) as being one of the five sacred

mauri or talismans, those things possessed of the soul of the Maori

people. It is referred to in the whakatauaaki or proverb

"Me ai ki te hua o te rengarenga me whakapakari ki te

hua o te kawariki" — may you be nourished by the

fruit of the rengarenga and of the kawariki2

(Williams 1992: 251).

Rengarenga

is recorded by Tregear (1926: 496) as being one of the five sacred

mauri or talismans, those things possessed of the soul of the Maori

people. It is referred to in the whakatauaaki or proverb

"Me ai ki te hua o te rengarenga me whakapakari ki te

hua o te kawariki" — may you be nourished by the

fruit of the rengarenga and of the kawariki2

(Williams 1992: 251). The

rafters of Maori wharenui (meeting houses) are often decorated with

elaborate scroll-like patterns known as kowhaiwhai. These usually

are painted in red, white and black, although the pattern shown

in Figure 5 is grey, brown and white. The motif of the patterns

in general, represent natural objects (Hamilton 1896: 118).

The

rafters of Maori wharenui (meeting houses) are often decorated with

elaborate scroll-like patterns known as kowhaiwhai. These usually

are painted in red, white and black, although the pattern shown

in Figure 5 is grey, brown and white. The motif of the patterns

in general, represent natural objects (Hamilton 1896: 118).

Rengarenga

was one of the plants used for the treatment of boils and abscesses

and Colenso 1868: 267 recorded that the roots of the rengarenga

were roasted and beaten to a pulp and applied warm to unbroken tumours

or abscesses. White (1883) recorded that the bottom or lower end

of the leaves is beaten into a pulp as a poultice to cure ulcers

or longstanding sores and to allay swelling of joints or limbs.

He also noted that the root of the plant was eaten in its raw state

to cure the itch, although he did not specify the exact nature of

this complaint.

Rengarenga

was one of the plants used for the treatment of boils and abscesses

and Colenso 1868: 267 recorded that the roots of the rengarenga

were roasted and beaten to a pulp and applied warm to unbroken tumours

or abscesses. White (1883) recorded that the bottom or lower end

of the leaves is beaten into a pulp as a poultice to cure ulcers

or longstanding sores and to allay swelling of joints or limbs.

He also noted that the root of the plant was eaten in its raw state

to cure the itch, although he did not specify the exact nature of

this complaint.