|

Sundials Sundials Australia

John Ward and Margaret Folkard explore the history, use, and range of sundials available today. The articles are based on their book, Sundials Australia, the second edition was published in 1996. Part

1 — Historical background to sundials Most of us know of a

garden containing an old sundial tucked away in a corner, surrounded

by flowers, quietly telling the time. Sundials in one form or another

have been used by different societies for more than 5,000 years.

The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC) stated in his writings

that sundials originated with the ancient Chaldeans and Sumerians

who lived in Babylonia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in

the region formerly called Mesopotamia and now known as Iraq (Gibbs

1976). They used vertical rods on their buildings as shadow casting

devices for telling the time and date, and were the first people

to divide the day into 24 hours, the week into 7 days, and the year

into twelve months (after first having divided the sky into the

12 signs of the zodiac.)

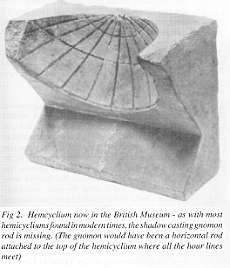

About 340BC Berosus,

a Chaldean astronomer-priest living in Egypt during the time of

Alexander the Great, developed the hemisphericum, in which a vertical

post was placed centrally inside a hollowed out hemisphere. The

inside surface of the hemisphere had vertical lines carved on it

to divide the daylight period into 12 hours, and horizontal lines

to show the seasons. The shadow cast on the inside surface of the

post marked out the path of the sun as it travelled across the sky. From this developed the

hemicyclium, shown in Figure 2, which was widely used throughout

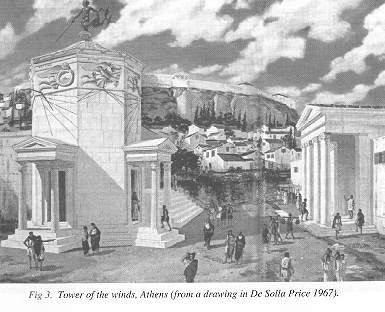

the civilised world right up until the 14th century. About 100BC the Tower

of the Winds (De Solla Price 1967, Aked 1992, Aked 1993, De Solla

Price and Noble 1968, and Figure 3) was erected in Athens at the

foot of the North Slope of the Acropolis. This is an octagonal tower

whose walls face towards the 8 cardinal directions North, South,

East, West, North-East, North-West, South-East and South-West. It

is so named because each wall features a carving with allegorical

representations of the wind which blows from that particular direction,

together with its name. Although it was primarily designed to contain

a Clepsydra (waterclock), a large sundial with a horizontal rod

gnomon was carved into each wall. The angle of the shadow on each

sundial told the time, while the length of the shadows told the

date, so the building acted as both clock and calendar. The Tower

is accurately aligned North-South, so the sundial markings on the

complementary faces (e.g., NE and NW) are repeated as mirror images.

The carved lines of the sundials were reported as being very faint

some 60 years ago, but today they are almost indistinguishable due

to the ravages of pollution and acid rain. After all this time,

it is not surprising that the gnomons are missing.

In the following centuries

the Greeks developed the sundial further, and experimented with

hemicycles, conical dials, cylindrical dials and flat dials set

at various angles. In those days, a system of unequal or temporary

hours was in common use, with the available period of daylight divided

into 12 parts — resulting in 12 long daylight hours in summertime

and 12 short daylight hours in wintertime. Astronomers, however,

used 'equal' hours (just as we do today) for charting the moving

heavens. The Romans are not believed

to have developed any new sundial types, but they certainly used

all the Greek sundial developments, and sundials were extremely

popular throughout their empire. Surviving specimens of Roman portable

sundials have been found designed for latitudes from Britain through

Narbonne in France to Ethiopia and Mauritius. The playright and poet

Titus Maccius Plautus (250-185 BC) produced the following verse

which demonstrates just how common sundials had become in Rome during

his lifetime (The English translation given here is taken from Mayal

and Mayal 1973): The Roman architect, engineer and writer Vitruvius mentioned 13 kinds of sundials including portable types, in the 9th volume of his work on architecture 'De Architectura Libri Decem'. This treatise, containing two chapters dealing with gnomonics was published in 27 AD but was later lost, and only rediscovered in 1486 (Granger 1931-1934). One of the sundials discussed by Vitruvius was the pelekinon, the type built by the Emperor Augustus in Rome in 9 BC which covered a vast floor area of 180m x 110m and used a 30m tall obelisk from Heliopolis in Egypt as its vertical gnomon. This particular sundial will be discussed in a later article.

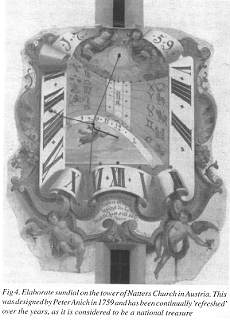

Although the Greek Aristarchus

had suggested 400 years before Ptolemy that the Earth and other

planets circle the Sun (Anon 1986), the Ptolemaic Earth-centred

theory was taken virtually as an article of faith right up until

the 16th century when it was replaced by the Copernican Sun-centred

system (Copemicus 1976). However, the Earth-centred concept is still

perfectly satisfactory for describing and designing sundials, so

we are probably the only members of the human race still sticking

to Ptolemaic principles! One of the many controversial dates in gnomonic history relates to when the gnomon of a sundial ceased being either vertical or horizontal, and was first inclined at the latitude angle to make it parallel to the axis of rotation of the Earth. Only when this happened could sundials tell time according to the system of equal hours. By the 14th century this method of constructing sundials had become common in Europe, and at about the same period mechanical clocks which divided the day into 24 equal hours started to appear. The early clocks were rare and very expensive, and not terribly accurate. They were often wrong by several hours and were frequently calibrated using sundials. Some mediaeval towns became famous because of their sundials — one example is Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Germany which still has many splendid sundials that were made long ago. In addition to telling the time using lines and numbers marked on a dial plate, sundials needed to have human appeal. Fine craftsmen developed high levels of artistic skill and decorated their sundials with embellishments of every kind. This artistic decoration, or 'furniture' as it is called, required many hours of labour to be carried out on both the dial plate and the gnomon (the part which casts the shadow). Many of these old sundials are now family heirlooms and very costly antiques which only museums and the like can afford to buy. As a direct consequence of the design difficulties and the labour required to produce a sundial, most people were unable to afford the high cost of such instruments. Consequently the owners of these enduring sundials throughout history have been the wealthy and public institutions such as cathedrals, parks and town halls. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate typical elaborate and consequently expensive sundials.Countless sundials have been designed and made in every conceivable shape, size and form. The most commonly used materials for these sundials were copper, brass, bronze and stone, materials chosen mainly because of their ability to resist corrosion and because skilled craftsmen could work in these materials using traditional techniques. The time-telling hour lines marked on these old sundials were carefully placed in position using intricate graphical construction techniques which were based on sound geometric theory developed over many centuries. Hundreds of ancient sundial books abound which describe in confusing detail how to 'lay-out' or draw a sundial. These geometrical methods are complicated, tedious and very time consuming. Fortunately such methods can now be totally discarded. The ready availability of computers and pocket calculators allows even complicated sundials to be accurately designed using simple mathematical equations derived from the basic principles of spherical trigonometry. (The formulae that allow you to do this yourself will be given in a future article).

References

Web-notes: For more information on sundials, John Ward and Margaret Folkard have published the book, Sundials Australia.

This book has briefly been reviewed on the RNZIH Horticulture Pages. It is available from Touchwood Books and listed by Sundials on the Internet (sponsored by the British Sundial Society) and the USA-based company SunPath Designs. |

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2024 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: May 17, 2003

From

The New Zealand Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand

Institute of Horticulture), Vol. 1, No. 4, December 1996, pp. 16-19.

From

The New Zealand Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand

Institute of Horticulture), Vol. 1, No. 4, December 1996, pp. 16-19.

The

Greeks and Romans in particular created a great variety of sundial

types and used them throughout their far-flung empires (Gibbs 1976).

In the following paragraphs we give a brief outline of some of the

most important events connected with time keeping in that part of

the world.

The

Greeks and Romans in particular created a great variety of sundial

types and used them throughout their far-flung empires (Gibbs 1976).

In the following paragraphs we give a brief outline of some of the

most important events connected with time keeping in that part of

the world.

In

150 AD Ptolemy of Alexandria (Ptolemaeus 1984, Peters and Knobel

1915) produced a book entitled 'He Mathematike Syntaxis ('The Mathematical

Collection') which 9th century Arabic astronomers renamed the Almagest

or 'Greatest Work'. In this work Ptolemy set forth his theory that

the earth is stationary and at the centre of the universe, and that

the Sun and the Moon and all the planets revolve around it. He also

showed how to draw the hour lines of a sundial by projection and

invented the analemma. His book was fortunate to survive the tragic

burning of the great library at Alexandria in the mid 7th century

AD.

In

150 AD Ptolemy of Alexandria (Ptolemaeus 1984, Peters and Knobel

1915) produced a book entitled 'He Mathematike Syntaxis ('The Mathematical

Collection') which 9th century Arabic astronomers renamed the Almagest

or 'Greatest Work'. In this work Ptolemy set forth his theory that

the earth is stationary and at the centre of the universe, and that

the Sun and the Moon and all the planets revolve around it. He also

showed how to draw the hour lines of a sundial by projection and

invented the analemma. His book was fortunate to survive the tragic

burning of the great library at Alexandria in the mid 7th century

AD.

Published

1996, 113 pages, A4 size, 90 black and white photographs and 100

line drawings. This authoritative book includes relevant facts about

the Earth, Sun and stars, and the various types of sundial, and

the relationship between sun and clock time. Formulae for calculating

hour lines are clearly listed. The blackness and sharpness of shadows

is discussed. There is also a collection of mottoes, a dictionary

of sundial terms, and a list of references. Price $A20 plus $A9

overseas postage.

Published

1996, 113 pages, A4 size, 90 black and white photographs and 100

line drawings. This authoritative book includes relevant facts about

the Earth, Sun and stars, and the various types of sundial, and

the relationship between sun and clock time. Formulae for calculating

hour lines are clearly listed. The blackness and sharpness of shadows

is discussed. There is also a collection of mottoes, a dictionary

of sundial terms, and a list of references. Price $A20 plus $A9

overseas postage.