|

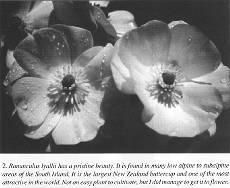

From The New Zealand Garden Journal (Journal of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture), Vol. 1, No. 2, June 1996, pp. 9-11. With increasing altitude, New Zealand mountain ranges present us with an interesting cross section of vegetation types. Lowland/montane forests of silver or mountain beech give way abruptly to a wide range of shrubs, snow tussocks, small or prostrate woody plants and low growing herbs. Mark and Adams (1995) state that between the tree line and snow line there is a greater range of alpine vegetation in New Zealand than in most other parts of the world. About 93% of New Zealand's alpine flora is endemic. Alpine plants are strongly adapted to the extreme climates found at high altitude. They often grow in infertile soil or shattered rock, with great changes in temperature from searing heat to extreme cold. They are often lashed by gale force winds. The low-growing, creeping, mat forming and cushion habit has obvious advantage in terms of wind resistance and repetitive snow falls are unlikely to damage such plants. Another feature of many alpine plants is a deep root system that provides a strong anchorage. Water and available nutrients often lie far below the surface in mountain habitats. Plants with deep root systems are better able to exploit available food resources. It may seem ironic to talk about mountain plants suffering from water stress. Yet despite high rainfall and water from snow melt many alpines are adapted to minimise water loss. This is because most alpine soils are very free draining, winds are frequent, and very high temperatures can occur during the summer months. New Zealand alpines have adapted to these conditions in many ways: For example, distinctive and unusual leaf characteristics are seen in many species of Aciphylla. Commonly called speargrass or wild Spaniard, these herbaceous plants with distinct whorls of narrow, spine tipped leaves and equally spiny flower stems present a xerophytic countenance. A few species of Carmichaelia or native broom, inhabit alpine areas. Such species are leafless and consist of short flattened branchless. I recall the difficulty of transplanting a specimen of Carmichaelia monroi because of its very long tap root. Hairy leaves are another way of limiting water loss on arid mountain sites such as screes. The hairs catch water droplets from fogs and low cloud. New Zealand's woolly vegetable sheep such as Raoulia eximia show this type of adaptation. Not only do the exterior leaves inhibit water loss, but within the cushion are the remains of old leaves which rot down to form a peaty, water-holding sponge. Growers attempting to grow this species in lowland areas need to take measures to prevent moisture clinging to the leaves, especially in humid conditions. Failure to do this can cause softening of leaf tissue leading to infection. The adaptations above are not exclusive to alpine plants but are found in other plants growing in harsh environments subject to a lack of water.

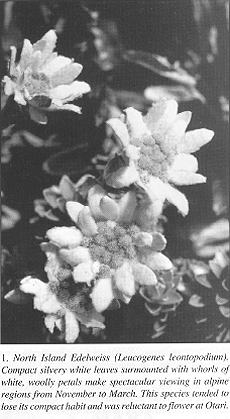

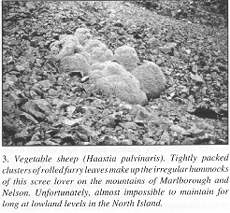

The alpine flora in many countries is highly coloured for instance Himalayan irises and primulas. New Zealand alpines are far less colourful with flowers often white or yellow. Never the less they are still attractive particularly with their range of growth habits and foliage. The 60 or so species of Celmisia cover most New Zealand mountain ranges. They are particularly eye catching when seen flowering en masse. As individuals, white flowering daisies do not enthral me. It is their foliage in which I find appeal. Many form rosettes of sword shaped leaves, ranging in colour from grey/green to silvery grey to silver itself. Perhaps none is more attractive in this regard than Celmisia semi-cordata with its conspicuous rosettes up to 1 metre in diameter. Some of the most distinctive alpines are the vegetable sheep. My favourite is the hummocked form of Haastia pulvinaris with its tightly rolled, compact, hairy leaves on terminal shoots, truly at a distance looking like vegetable sheep. Other noteworthy plants of the alpine zone include North Island edelweiss, forget-me-nots, buttercups, harebells (Wahlenbergia spp.), plus plentiful displays of the graceful snow tussocks which tend to dominate the low alpine areas. Cultivation How do these plants from high mountains react to being grown in lowland gardens? Their performance will be related to:

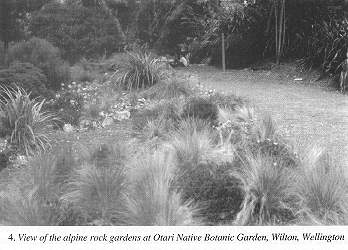

At the Otari Native Botanic Garden the site chosen for growing alpines had a southern aspect. On the north side nearby trees 10-15 metres high formed the periphery of the bush. Dry northerly winds are thus cooled and moistened as they pass through. The trees also provide shade from the afternoon sun. Drainage material such as small rocks and gravel was placed in a layer 15-20 cm thick at a depth of 45 cm. A 5 cm layer of coarse sand overlays the lower course. On top of this was the rooting medium containing a mixture of:

Once the medium had been added and shaped, rocks were placed. I grew alpines in this garden for over 20 years and many performed well, especially some celmisias such as Celmisia spectabilis and C. incana. The only trouble with C. incana was that in spite of heavy flowering annually, the resultant seeds were not viable. Some of the gems of the flora I found difficult to maintain. Gentians proved almost impossible to keep going for more than two years. Some woody plants lived but failed to flower, for instance Dracophyllum recurvum.

Small plants grown in containers in a shade house often performed better than their counterpart growing in the alpine beds. The main cause of death was damping off. Conditions that were thought to promote ill health and short life spans included:

My final assessment is that cultivation of alpines in lowland parts of the North Island will always be a challenge with some species always performing better than others. It is a matter of trying a range of sites and soil conditions to see which perform best for you.

Mark, A. F.;Adams, N.

M. 1995: New Zealand Alpine Plants. Godwit Publishing, Auckland. Foot note The late Ray Mole, AHRIH, was Curator of Otari Native Botanic Garden from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. He died in 1995.

Web-notes: Alpine Garden Links

|

Home | Journal

| Newsletter | Conferences

Awards | Join

RNZIH | RNZIH Directory | Links

© 2000–2025 Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture

Last updated: March 1, 2021

Reproduced

from an article by Raymond Mole

Reproduced

from an article by Raymond Mole True

alpines have a comparatively short growing season. They need to

grow, flower and produce seed between snow melt and fresh autumn/winter

snowfall. In Norway, Ranunculus nivalis has been

recorded in flower five days after snow melt and produced ripe fruit

seventeen days later.

True

alpines have a comparatively short growing season. They need to

grow, flower and produce seed between snow melt and fresh autumn/winter

snowfall. In Norway, Ranunculus nivalis has been

recorded in flower five days after snow melt and produced ripe fruit

seventeen days later.

The

turn over in the alpine section was much greater than in other Otari

collections. The main exceptions were tussock grasses, Pentachondra

pumila, Ranunculus insignis, hebes, some celmisias including

those mentioned, and certain helichrysums, especially H. selago.

Raoulia hookeri was particularly easy and is an example of

a species with a wide distribution from coastal to alpine areas.

It seems that species with a wide altitudinal range are easier to

grow in a temperate garden.

The

turn over in the alpine section was much greater than in other Otari

collections. The main exceptions were tussock grasses, Pentachondra

pumila, Ranunculus insignis, hebes, some celmisias including

those mentioned, and certain helichrysums, especially H. selago.

Raoulia hookeri was particularly easy and is an example of

a species with a wide distribution from coastal to alpine areas.

It seems that species with a wide altitudinal range are easier to

grow in a temperate garden.